83 years ago, the New York Times printed Raymond Torrey’s description of the Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail.

Today, instead of a pretty stream at the Suffern end of the trail, there’s an interstate. The Palisades Parkway now cuts through the trail below Pyngyp Mountain. And the old copper trail markers have been replaced by paint spots and plastic squares*.

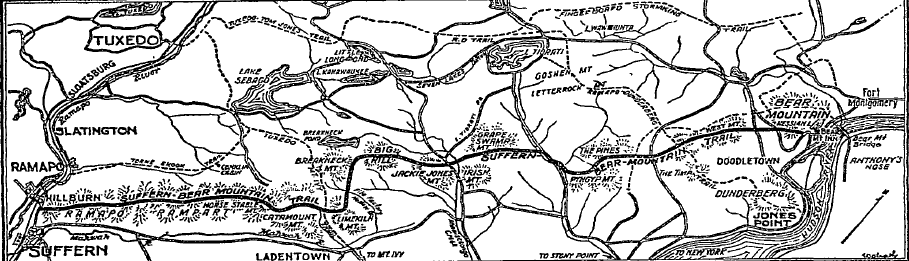

The map that introduced New York hikers to the Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail, in Harriman State Park. The article, by Raymond Torrey, was published in 1927. The map alone makes me want to hike the length of the trail.

But it’s still a vigorous, challenging trail, calling to hikers. Read Torrey’s article below:

The New Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail

(reprinted from the New York Times, 1927

“The Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail, the ninth of such footpaths for hikers made during the last seven years by volunteer workers form the New York City metropolitan district walking clubs in the Harriman State Park, in the Highlands of the Hudson and in the Ramapo Mountains, is now almost complete. It discloses new scenic viewpoints and new aspects of the hills and forests, lakes and streams of this 40,000-acre preserve.

“This new trail is twenty-four miles long, following the curves of ridges, dipping into gaps for springs and waterholes, yet pursuing a course intended to combine with scenic values a reasonable degree of directness. It begins at Suffern, on the main line of the Erie Railroad, thirty miles from New York, and follows the Ramapo Rampart, the long straight front of the Ramapo Montains. Then it angles back to another parallel northeast-southwest ridge and runs north and northeast to the headquarters of the Harriman Park, at Bear Mountain.

“It will be a hardy hiker who does all of this trail in one day, for it rivals in ruggedness the Ramapo-Dunderberg Trail, twenty-five miles long, from Tuxedo to the Hudson, which few walk at a stretch; but it offers fine sections from five to fifteen miles in length that can be reached at various points by train or bus.

Trail Markers

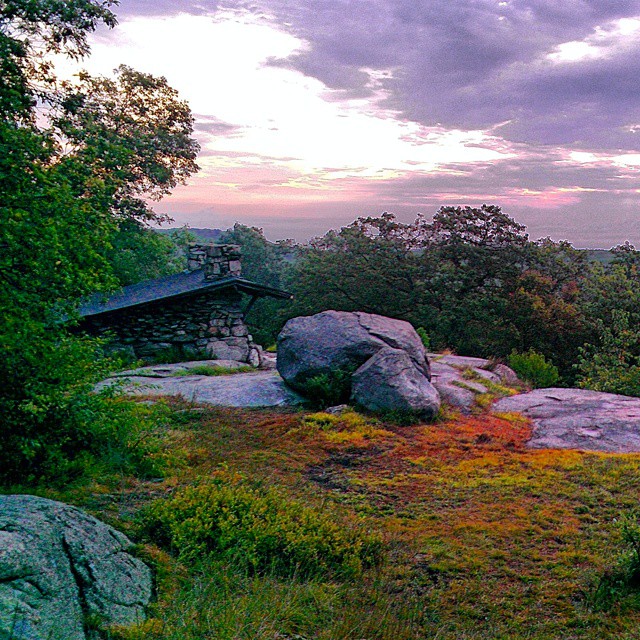

Big Hill Shelter, along the Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail. Photo by Andrew Lois. (Follow Andrew’s brilliant Instagram pictures, here: http://iconosquare.com/andrewclois)

“The new trail is marked as are others in the Harriman Park, with metal squares bearing a symbol and the initials of the termini of the route. On this trail copper squares, with the initials S-BM and a diamond are used. A new method of securing lasting qualities of such a marker has been adopted by Major W. A. Welch, general manager of the Palisades Intersate Park, who provides the signs and has encouraged the volunteer workers in this interesting combination of their usual hiking excursions with a definite object in view.

“To begin at the south end of the Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail, the hiker should go west from the railroad station at Suffern, past the last of the gasoline filling stations on the left, and turn right, into a little amphitheater, between two conspicuous granite ledges that abut the highway. The trail climbs up a ravine to a ledge which gives a fine view south over the valley of the Ramapo and the mountains westward toward the Wanaque Valley; then turns right to another viewpoint out east, over the lowlands of Bergen County, N.J., and Rockland County, N.Y.

“Just north of the second viewpoint, an old road is picked up, which follows the summit. For the first half-mile the route is marked with cairns and paint blazes, but presently the copper markers begin and may be followed thereafter. The trail drops into a notch in a cutover woodlot; then climbs again up a cliff which the trail markers have called the Kitchen Stairs; then on over a level plateau, dipping into a cattail swamp; then up again, and out to another viewpoint over the Rockland County rolling farmlands, with the Palisades and Hook Mountain in the background.

“From this view the trail turns left — westward — to gain a crossing of a rocky notch in the Rampart without descending too much. This notch, filled with boulders of all sizes, has been called by Frank Place, President of the Trump and Trail Club and one of the chief workers on the trail, the Valley of Dry Bones, a name that has stuck. From this gap the route climbs eastward again to another open viewpoint: a ledge with an interesting geological feature, a curiously branching dike of diabase in the midst of the granite of the summit.

“The trail passes on north, through the brush grown fields of a long-abandoned farm; then to a rocky ridge heaped with huge boulders in picturesque confusion, some of them twenty feet high and among the largest of those transported by the ice in this region. This boulder field has been called MacElvaine’s Rocks, after a member of the Fresh Air Club, who most ingeniously laid out the route here to make it as rocky as possible.

Cliffs and Boulders

“On the next summit northeast the trail climbs past a steep cliff called the Hangman’s Rock, which looks much like the setting in the final scene of “Turnandot.” This mountain gives another view east. Beyond, the trail dips into a gully where there is a spring, and then climbs Pierson Mountain, past a good example of a “propped rock”, where a small boulder melted out of the ice sheet that covered the Ramapos 2,000 feet deep, to serve as a prop for a much larger block that dropped later on.

“The trail curves around to the west side of the mountain, giving a good view west over the interior valleys of the Ramapo Plateau, including the Mountaineer’s Meadow and Conklin’s Cabin — the only occupied house in the region — and the leggy slopes of Halfway Mountain.

“On the next descent the trail includes a remarkably polished protruding ledge, known as the Egg, later crossing a brook, which provides another good luncheon place. Climbing Horsestable Mountain, past a clump of cubical boulders, the trail passes along the cliffs of Hawk Rock and enters an old wood road at a large white oak, spared as a corner mark of some property line. The road turns northeast and then to the left, proceeding downhill into a deep gully between Catamount and Panther mountains. The trail route around the outside of Panther gives many fine “windows” out to the country eastward and presently brings into view the Hudson, over the ridge of the Tors — Haverstraw Bay, with the Westchester hills beyond.

A Westward Turn.

“The trail now curves around westward, over a brook hidden by tumbled boulders, crosses the Tuxedo-Mount Ivy Trail, climbs to Eagle Rock, passes over knobs scarred by fires, and descends to use an old path known as the Red Arrow Trail. This trail follows northwest across File Factory Hollow Brook, the Woodtown Trail and Ladentown Mountain, to Breakneck Mountain, which gives views east to the Hudson and west over the lakes and and hills of the interior of the park and beyond toward Greenwood Lake. It pursues this ridge northeast to a northern point known as Big Hill, where there is a sort of balcony of open ledges with a splendid outlook to the Hudson.

West Mountain Shelter is just off the Suffern-Bear Mountain Trail in Harriman State Park, just before you reach Bear Mountain State Park. It’s most often used in summer by thru-hikers on the Appalachian Trail. A favorite.

“The S-BM now descends, crosses the Old Turnpike and climbs to the fire observation tower on Jackie Jones Mountain, where one can see the skyscrapers of Manhattan, thirty-five miles to the southeast. It follows a path down to the corner of the Gate Hill Road and the old Lake Tiorati (Cedar Pond) Road, which it uses a short distance north to cross the north branch of Minisceongo Creek. Just beyond the creek at a set of bars the trail turns to cross the pastures northward and passes through another set of bars at the edge of the woods. On the other side is an old road used by the Boy Scouts as the rim of their White Bar Trail and adopted here by the S-BM. This leads over Grape Swamp Mountain and down to the Lake Tiorati Brook Road, with a fine view out northward.

A Historical Road

“Eastward, to the right for half a mile the road runs past the bridge over Lake Tiorati Brook, and then the hiker turns in to the left to look for stepping stones over the stream. The trail climbs up the steep, pine clad cliffs of Pyngyp, for more fine views. It drops into a gap, then climbs the next summit, The Pines; descends again, and crosses the old road over which Anthony Wayne led the Continentals to the storming of Stony Point in 1779.

“Soon it reaches the Ramapo-Dunderberg Trail (marked “R-D” with a red dot) at the bottom of the cliffs on the south side of West Mountain; it uses this trail to climb to the summit, where it resumes its own course northward.

“Crossing the swampy notch between the south and north crowns of West Mountain, the trail climbs a zigzag route up a cliff called the Fire Escape, and at the top enters the Timp-Torne Trail, marked with a square and the initials “T-T.” It uses the T-T a few rods north, then leaves it at an angle and descends to the bottom of the notch, which cuts off from the main mass of West Mountain a high eastern shoulder, with cliffs on its south and east faces; follows the brink of the cliffs, around northward, with views of the Hudson gorge; descends a steep talus slope; entered a cutover area; drops to a pretty brook which comes off the amphitheater in the centre of the mountain, and follows it on the left side, downhill to a sharp left turn through another notch.

“After crossing two more brooks, the way leads up to the old Doodletown Road, over which Sir Henry Clinton sent his flanking body to assault the American forts Clinton and Montgomery in 1777. This it crosses and then makes its way east, crossing the Seven Lakes Drive, the main park motor highway, and descends to the outer curve of the drive, at the foot of Bear Mountain, a few hundred feet west of the park headquarters. A large lettered sign marks the north end of the trail and similar signs have been placed at important points elsewhere along its route.”

Raymond H. Torrey, “Stiff New Trail Calls to Hikers”, The New York Times, May 1, 1927.

*I’d love to find one of those old markers on Ebay one day…

Lots of information I didn’t know about. Lived in the area as a growing child. How lucky can one person be.

I’m very curious about the look/design of the original trail markers. Does any one have any archival images or more info on what they looked like?

I like it very much…