Did you think there was only one treasure legend in Harriman State Park? (I did.)

Looking for the source of the name “Letterrock Mountain”, I found an intriguing article in the New York Times from 1934. It started this way:

“Musty legends, yellowed maps, dark little gnomes and a mysterious Bronx syndicate of silver hunters figure in the story.”

The article told of mysterious sounds of explosion coming from the vicinity of the mountain for a period of months in the summer of 1934.

Was it coming from neighboring West Point? If you’ve been to the northern section of the park or Bear Mountain, you might be familiar with the distant sound of explosions like thunder, as the soldiers of West Point are on maneuvers.* But it wasn’t that.

“William Gee, chief ranger, and a man who knows his Washington Irving, was a bit uneasy. He recalled the legend of the gnomes in “Rip Van Winkle” and the flagon-quaffing little men who make thunder with their ninepins, but decided to leave them out of his speculations.”

So now I’ll let the Times’ anonymous journalist on the treasure-hunting beat in the 1930s do the storytelling. (I later found out that the “gnomes” of this story were actually quite tall. But I’ll let it slide, because I now know that valuable adjective, “flagon-quaffing”.):

“Finally, after many months, his men came upon a fresh scar — huge and widespread — on the side of old Letterrock, and in a deep hole in the ground, not far away, a cache of mining tools, pneumatic drills, hammers and a load of dynamite. They confiscated the stuff.

“For weeks the rangers and the Bear Mountain State police tried to fill in the puzzle. Who had blown away the mountainside, and why? They gave it up, finally, but kept on watching. On the morning of October 27 one of the rangers saw four little men, all hunched under heavy loads of mining tools and more dynamite, toiling up the rude trail of the mountain.

“Word was relayed back to Chief Ranger Gee. He concealed his men to see what would happen.

“The little men put their loads down carefully, listened awhile for suspicious sounds, and, hearing nothing but the sighing of Autumn leaves, set to work. One drilled a hole in the mountainside, another plugged it with dynamite, a third set a match to the fuse.

“The little men backed away to a safe distance, the charge went off, the countryside rocked with the detonation and the echo rolled back like thunder.

“Chief Gee and his men, at this point, came out of their concealment, surrounded the little men and told them to drop their tools. Sullen and dark with anger — these little men were not fair, like Rip’s companions — the strangers obeyed, but when the head ranger and the troopers questioned them they gave no answers.

“As they marched their glowering prisoners down Lake Tiorati Brook Road they came upon a large motor truck, hidden deep in the trees to one side. It carried more dynamite and more tools. Apparently the little men had left it there to throw off suspicion and had hiked the rest of the way up the mountain.

“Sergeant James Gazaway and Chief Ranger Gee questioned their prisoners for hours, but they remained tight-lipped and surly. The first indication of their mission in the mountain, and the reason for the great scar in old Letterrock, came from a curious contract, copies of which were found on each of the prisoners.

“Sergeant Gazaway could not recall yesterday the exact working of the document, but in substance, he said, it bound each of the persons carrying a copy to turn over to the “undersigned” whatever treasure they found in the lonely rocks of Letterrock.

Saw Map in Morgan Library.

“Slowly, then, the men admitted that they had been hired to hunt for a great hoard of silver bars and barrels of ancient silver coins hidden somewhere in a cave there. The secret of the spot and how to reach it, they insisted, came out of a faded map in the Morgan Library in New York.

“‘They told us,’ the sergeant said, ‘that they were sent in there, a few at a time, to blast away the mountainside in the hunt for the cave. They tried, whenever possible, to time their blasts with the blasts of CWA workers who were putting a road through the park some distance away, so that we wouldn’t get suspicious.’

“Who the ‘master mind’ was behind the treasure hunt the men would not tell, according to Major Welch and the troopers.

“Major Welch remembered yesterday that early last April Governor Lehman forwarded to him a letter from a man named Charlies W. Wenk of 516 East 118th Street in which the writer had asked permission to search for a cave in the Harriman section of the park which he believed contained treasure.

“The Major answered the letter, promised to send the chief ranger and another man into the forest with Wenk, but told him he did not believe there were any caves of extensive size in the territory. No answer ever came from Wenk and the matter was dropped.”

Tale of the Cave Revealed

“Down by the river, in one of a row of small houses that huddle close together in the dark, in a neighborhood lit last night by little boys’ bonfires, Charlies Wenk was discovered. He is a little man, with intelligent features in a childishly round face, soft speech and cultured bearing.

“At first he was startled by the story of the arrest of the little men on Letterrock. Then he called through the dim-lit apartment to “Yvonne!”. A woman emerged from the shadows and listened silently to the interview.

“‘Of these things,’ said Wenk, ‘I know nothing. How these men found this place I cannot understand. I have spoken to no one about my letter to the Governor. I was not prepared at this time to begin my hunt for the treasure.'”

“Then, bit by bit, he told how he came by the secret of the cave. It seems that George Gyra, with whom he worked some years ago int he Vanderbilt Garage in Thirty-third Street, near Lexington Avenue, came home one day last Spring, from a CWA project int he Interstate Park where he had been employed, with the story of the cave.

“‘He wandered away from the other CWA workers at lunch time one day,'” related Wenk, talking with a trace of foreign accent, his face all in shadow in the poorly lighted room, ‘and quite by accident found a small crevice in the mountainside. It was barely large enough to admit a man, but he crawled inside. He got in six or eight feet and it was all dark.

“‘He lit matches, but they made hardly a splash in that great dome of darkness. He picked up stones, when he was able to stand erect, and pitched them as far as he could, trying to hit the opposite wall, but they didn’t hit. Then he crawled out again.’

“Wenk hesitated a moment.

“‘There was another man with him,’ he muttered. ‘He might be the one who told the story, and that’s how those men came to be blasting there — that is, if they were at the same spot. I don’t know. I’ve never been there, yet. And I might as well tell you — George said that when he got out into the light again he found bits of silver of gold clinging to his breeches.’

“‘He made a sketch of the spot and came home and told me about it, and I said: “There’s only one way to go about this, George; we must write to the Governor,’ and I did. That’s where I come in. We were going to go there when my health was better. We’d be allowed to keep at least part of the treasure if we found it, wouldn’t we?’

Section Rich in Rumors

“Major Welch said the whole territory around Letterrock was rich in legends of buried treasure. One tells of a lode called Spanish Silver Mine, on Black Mountain, a mile east of Letterrock, where Spaniards who came up from the West Indies were supposed to have mined great fortunes in silver.

“As for the letter from the Morgan Library, he thinks he knows that, too. He has a copy which is dated 1690 or around that period. It is old and yellowed, cracked in the folds, and in several pieces.

“It says, in part:

“‘Start at Samuel More’s landing and go to Belcates, which is three miles across the mountain that leads to New Windsor. You follow marked oak trees, and when you get on the mountain, turn to the right hand. Keep on till you come to a bog meadow. You cross an old dam. Keep on until you come to old Indian fields, then Stony Brook. Keep up that brook half a mile, then turn to the right hand to a brook that leads between two mountains.

“‘Keep down that brook one mile until you come to some large rocks. Then you are close to the mine. In the mine is bars of silver and two barrels of dollars. In a crack on of the rock is the bars of silver hid. This brook empties into the Hudson River.’

“These directions, says the major, are rather vague, but if the writer meant the stream now known as Stony Brook, its highest waters rise two miles west of Letterrock Mountain, but any one going up the brook and crossing to a stream flowing into the Hudson might possibly reach Stillwater Brook, south of Letterrock.”

One More Article

Cool, huh? But I still didn’t know where the name “Letterrock” came from. Or who hired the men to blast the stuffing out of the mountain. And then I found another article, dated the following day:

“The four amateur treasure hunters who spent months blasting away at the hardest kind of granite on Letterrock Mountain in Palisades Interstate Park showed a zeal and confidence worthy of a less-hopeless cause, William H. Carr of the American Museum of Natural History said yesterday. Mr. Carr is director of the museum’s Trailside Museums, a few miles from the scene of the treasure hunt, and saw the hunters an hour or so after they had been found by park rangers and State police.

“One of the men, he said, actually wept when it was finally borne to him and his companions that their search was over, without result. Mr. Carr described the four as being between 50 and 60 years of age, quite tall, and apparently not miners, although they knew how to employ the hand drills and dynamite with which they had succeeded in blasting a deep hole in the solid granite.

“Their conviction that there was a huge cave, filled with the bodies of massacred Indians and the treasures of Spaniards now dead for centuries, to be found at the end of their hunt was so great and so obvious that he wondered himself if they might not be right, Mr. Carr recalled.

Rock Described in Map

“The unhappy hunters told of a map on which was described a large rock, shaped like an arrowhead, and marked with geometric designs, he said. This rock pointed to a cave where, centuries ago, Spaniards had secreted the bodieds of 3,000 Indians whom they had killed; then, liking the qualities of the hiding place, the same Spaniards buried their own valuables in it, the men asserted.

“Then they pointed to a huge glacial boulder, shaped like the one described, and with markings they said were identical with those shown in the map. It all looked plausible, said Mr. Carr, but for one thing. The marks on the rock had been caused by weathering, and there were similar ones on the other boulders in the vicinity; but that did not deter the treasure seekers.

“They were just as sure as ever that there was a cave beneath the thirty feet of stone they were dynamiting, and they begged permission to search for six weeks more — they even offered $5,000 of their mysterious backer’s money for the privilege. But the park authorities were determined; the men had to leave.

Officials Try Own Test

“But Mr. Carr and John T. Tamsen, superintendent of the section of the park in which the hunt had been carried on, were impressed. They got some dynamite and set it off to make sure that Letterrock did not have just such a cave as the men had been seeking. (say what?? — Suzy)

“The way to find out if there is a cave in some locality is to set off a blast and lie flat on the ground, listening intently. If the vibrations have a certain tone, there is a hollow near by; if they sound steady and solid, there is no cave. Mr. Carr and his companions heard somber, forbidding vibrations; there was no cave.

“The men lived in a neat camp, each with his own cot and mattress, Mr. Carr recalled. They had a large supply of canned goods, and a liverwurst and a ham were suspended carefully from the ridgepole of their tent, away from small animals. They were prepared to stay as long as necessary to bore through the granite.”

Published in the New York Times, November 10, 1934.

Today’s Map

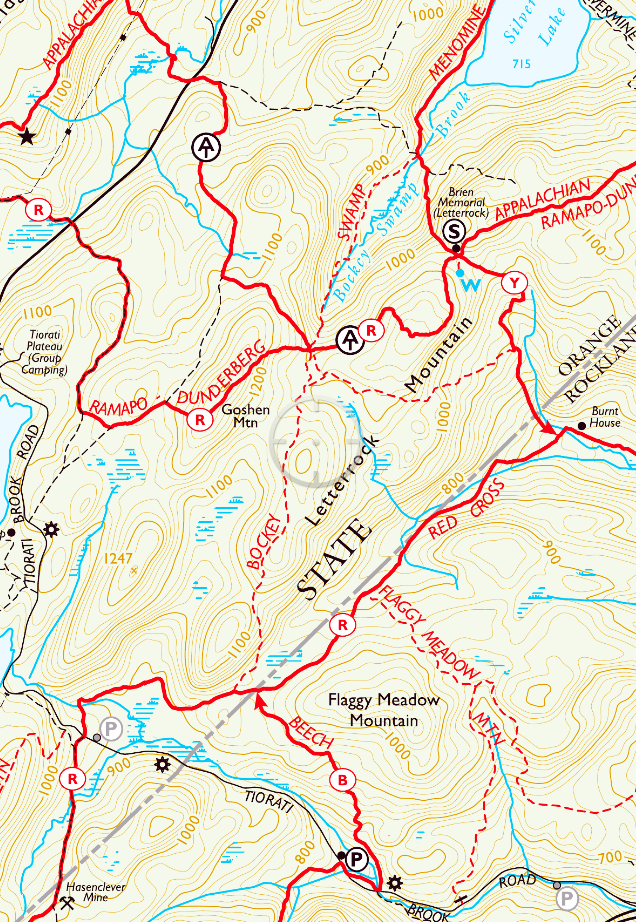

This is the modern-day map, by the New York – New Jersey Trail Conference, of the area described in this article. See a place where the brook flows between two mountains? I see several.

You can hike the area to scout for the gash in Letterrock created by these four men (dwarfs, gnomes, little people) by parking on Tiorati Brook Road (closed in the dead of winter) in the parking area just east of Lake Tiorati, where the road bends away and intersects the Red Cross Trail. Hike the Red Cross Trail to the Bockey Swamp Trail, an unmarked path that leaves to the left just before you reach the blue-blazed Beech Trail.

Why not? Try to find the “Lettered Rock” of Letterrock Mountain — it’s shaped like an arrowhead, and points to a cave. They say.

I wonder….where is that map now?

*Yesterday I hiked Turkey Hill Lake and the explosions were so frequent I stopped hearing them. I passed another hiker and we talked about West Point. He grew up in the area, and told me that as kids, they’d sneak onto the training ground and play in an area called “Viet Cong Village”, a mock Viet Nam village that served as a firebase for their Field Artillary Unit training.

Great story, excellently written article. Thanks.

This is positively FASCINATING!!! I love the old tales of Harriman and the old Iron Mines.

Thank you!

Thank you, Carol. Now I’d love to also find that map!

Interested to know why me in particular.

Your blogpost came to me during a hectic couple of weeks this summer. I saw the title, read the first paragraph, and immediately put the brakes on. No, this was something to be savored. To be pored over and given a proper batch of time. Well, I just got ’round to reading it, and I wasn’t disappointed. What a great tale to stumble upon in your research. This is internet journalism at its finest, Suzy. Bravo!

Robert, thank you so much. I wish the reporter had been credited under the story in the Times’ archive. (My sister is sitting next to me now, bugging me to go up the mountain and find the treasure. )

Thanks!

Well, there’s plenty of daylight left. Dig through the garage for some pick axes. If you don’t find any treasure today, be assured that the two of you will share a memorable day that will be worth it’s weight in gold as the years pass.

Well, I just read the story and find it interesting. I’ve done some metal detecting & digging here in North Rockland, and have found several items from over 100-150 years ago. Might be interested in checking it out.

Pete: A clue from the letter from the 1600s: Look for the large rock that looks like an arrowhead. :0)

I would be interested in seeing pictures of any items that treasure seekers find In the park..